An Unearthly Series - The Origins of a TV Legend

Saturday, 23 November 2013 - Reported by Marcus

The final episode in our series of features telling the story of the creation of Doctor Who, and the people who made it happen.

The final episode in our series of features telling the story of the creation of Doctor Who, and the people who made it happen.On Saturday 23rd November 1963, at 5.16pm, exactly 50 years ago, Doctor Who was first broadcast on BBC Television.

The story so far... Since the spring of 1962, a new science-fiction series has been slowly, but sometimes surely, growing into life at the BBC. From the vague suggestion that the Corporation should look at making such a series, through brainstorming sessions, a new head of drama, script problems, re-made episodes, the threat of cancellation and constant arguments over budget and resources, the absolute determination of a small but determined production team has seen the new programme, called Doctor Who, at last ready to face the sternest test of all - the opinion of the British viewing public, on a day when world events have left most of them likely to be too shocked to take it in at all...

Despite events in Dallas, the schedules on BBC Television for Saturday were relatively unaffected by the news. It was the days before rolling news and continuous live updates. Grandstand, the long-running sports programme, was on air as usual, with live coverage of rugby union, where Cardiff were playing New Zealand, forming the bulk of the afternoon. A 1'47" news flash had been broadcast at 4pm, with Corbet Woodall bringing viewers up to date with events from America. Grandstand came off air just after 5.15pm and was followed by a 50-second presentation junction looking ahead to the evening's entertainment, which included Juke Box Jury, with Cilla Black, Sid James, Don Moss and Anna Quayle, the police series Dixon of Dock Green, the American series Wells Fargo and the Saturday film Santa Fe Passage.

Despite events in Dallas, the schedules on BBC Television for Saturday were relatively unaffected by the news. It was the days before rolling news and continuous live updates. Grandstand, the long-running sports programme, was on air as usual, with live coverage of rugby union, where Cardiff were playing New Zealand, forming the bulk of the afternoon. A 1'47" news flash had been broadcast at 4pm, with Corbet Woodall bringing viewers up to date with events from America. Grandstand came off air just after 5.15pm and was followed by a 50-second presentation junction looking ahead to the evening's entertainment, which included Juke Box Jury, with Cilla Black, Sid James, Don Moss and Anna Quayle, the police series Dixon of Dock Green, the American series Wells Fargo and the Saturday film Santa Fe Passage.  It was at exactly 16 minutes and 20 seconds past five that the opening titles of Doctor Who ran and the nation was introduced to a brand-new science fiction series.

It was at exactly 16 minutes and 20 seconds past five that the opening titles of Doctor Who ran and the nation was introduced to a brand-new science fiction series. The ratings were sound, but not spectacular, with 4.4 million viewers tuning in. A power cut had hit a sizeable area of the country, meaning many people had been unable to watch, and for this reason executives agreed to repeat the first episode a week later, just before transmission of the second.

Press response, however, was favourable, as was the BBC's own audience research into the story. A Reaction Index of 63 was recorded, roughly the average for drama at the time. Detailed research, released in December, showed viewers in a research sample thought this a good start to a series that gave promise of being very entertaining.

AUDIENCE RESEARCH REPORT

AUDIENCE RESEARCH REPORT'Tonight's new serial seemed to be a cross between Wells' Time Machine and a space-age Old Curiosity Shop, with a touch of Mack Sennett comedy. It was in the grand style of the old pre-talkie films to see a dear old Police Box being hurtled through space and landing on Mars or somewhere. I almost expected to see a batch of Keystone Cops emerge on to the Martian landscape. Anyway, it was all good, clean fun and I look forward to meeting the nice Doctor's planetary friends next Saturday, whether it be in the ninth or ninety-ninth century A.D.' wrote a retired Naval Officer speaking, it would seem, for a good many viewers in the sample who regarded this as an enjoyable piece of escapism, not to be taken too seriously, of course, but none the less entertaining and, at times, quite thrilling - 'taken as fantasy it was most enjoyable. I presume it is meant for the kiddies but nevertheless I found it entertaining at Saturday teatime and look forward to seeing the Cave of Skulls in the next episode'. Some viewers disliked the play, either because they had a blind spot for science fiction of any kind or because they considered this a rather poor example, being altogether too far-fetched and ludicrous, particularly at the end - 'a police box with flashing beacon travelling through interstellar space - what claptrap!' Too childish for adults, it was at the same time occasionally felt to be unsuitable for children of a more timid disposition and, for one reason or another, proved something of a disappointment to a sizeable number of those reporting. Generally speaking, however, viewers in the sample thought this a good start to a series which gave promise of being very entertaining - the children, they were sure, would love it (indeed, there is every evidence that children viewing with adults in the sample found it very much to their taste) but it was, at the same time, written imaginatively enough to appeal to adult minds and would, no doubt, prove to be quite intriguing as it progressed.

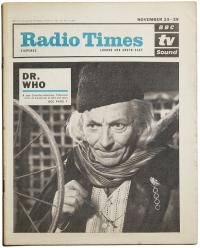

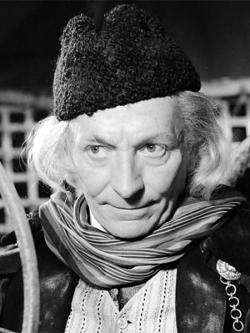

The acting throughout was considered satisfactory, several viewers adding that it was pleasant to see William Hartnell again in the somewhat unusual role (for him) of Dr. Who, while the radiophonic effects were apparently highly successful in creating the appropriate 'out of this world' atmosphere, the journey through space being particularly well done.

TELEGRAM

To: SYDNEY NEWMAN. WARWICK HOTEL. 65 W 54th STREET, NEW YORK.

Date: 27 NOVEMBER 1963

DOCTOR WHO OFF TO A GREAT START. EVERYBODY HERE DELIGHTED REGARDS DONALD.

To: SYDNEY NEWMAN. WARWICK HOTEL. 65 W 54th STREET, NEW YORK.

Date: 27 NOVEMBER 1963

DOCTOR WHO OFF TO A GREAT START. EVERYBODY HERE DELIGHTED REGARDS DONALD.

When the series went on the air it had a very uncertain future. Just 26 episodes were confirmed, with an option for an additional 13 if it did well.

With hindsight, that future was secure and the series would flourish. The arrival of the Daleks at the end of the fifth episode would capture the imagination of the nation and push the series to the forefront of British consciousness. Ratings for the first year would peak at over 10 million viewers and the series would become an important weapon in the BBC's battle to win dominance of Saturday night against rival ITV.

The show would survive many changes: the loss of the first production team, the changing of the companions, and in 1966 the replacement of the lead actor. It would survive the transformation into colour and being shunted around the schedules. Ratings would veer from a disappointing 3.1 million to an astonishing 16 million. Most importantly, the series would beat cancellation in 1989, being reborn in 2005 for a new generation, having been brought back to life by those who had adored it in their youth, allowing fans across the world to experience the wonder of the show, just as their parents and grandparents had done before.

Today, Doctor Who celebrates its 50th anniversary with a global broadcast of the 799th episode The Day of the Doctor. The series is at the heart of the BBC's strategy for the future. It brings in millions of pounds for the Corporation through overseas sales and merchandise deals. It is at the centre of the BBC's Saturday night schedule and breaks all records for digital engagement. Eleven lead actors have now graced our screens as the Doctor, with the 12th lined up to take over next month. The series that started life as a vague idea from a working group in 1962 is now an international phenomenon. If all the episodes were shown back to back, the screening would last for 15 days, 10 hours and 9 minutes. It holds the Guinness World Records for "the world's most successful sci-fi series" and "the world's longest-running sci-fi series".

But more than all the awards and accolades, Doctor Who holds a very special place in the hearts of the people who love it. Something about Doctor Who touches the very soul, inspiring generations of fans in their love for the series. The first 50 years are complete. The story goes on.

SOURCES: The Handbook: The First Doctor – The William Hartnell Years: 1963-1966, David J Howe, Mark Stammers, Stephen James Walker (Doctor Who Books, 1994); Radio Times Vol 161 No 2089; BBC Written Archives. The Genesis of Doctor Who

The news from Dallas did not come until the evening, so on the morning of Friday 22 November 1963 - exactly fifty years ago today - the Doctor Who production team had other matters on their minds. Earlier in the week, the Head of Serials

The news from Dallas did not come until the evening, so on the morning of Friday 22 November 1963 - exactly fifty years ago today - the Doctor Who production team had other matters on their minds. Earlier in the week, the Head of Serials  Spurred by this, Wilson wrote to

Spurred by this, Wilson wrote to

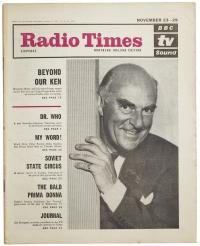

One of the best ways for the BBC to promote its programmes in the 1960s was through its own weekly listings magazine, the Radio Times. The magazine was almost as old as the BBC itself, having been launched in 1923, just one year after the BBC began transmissions. In 1963 it turned forty, and was already something of a national institution. Until the deregulation of the TV and radio listings industry in the early 1990s, it was the only place where readers could find detailed information about all of the BBC's programmes for the full week ahead. It was therefore one of the UK's best-selling magazines, most of the population had at least a passing familiarity with it, and it was both a valuable source of revenue for the corporation (unlike on television or radio, the BBC could sell advertising in the pages of the Radio Times) and a tremendous source of publicity, of immense value in promoting programmes.

One of the best ways for the BBC to promote its programmes in the 1960s was through its own weekly listings magazine, the Radio Times. The magazine was almost as old as the BBC itself, having been launched in 1923, just one year after the BBC began transmissions. In 1963 it turned forty, and was already something of a national institution. Until the deregulation of the TV and radio listings industry in the early 1990s, it was the only place where readers could find detailed information about all of the BBC's programmes for the full week ahead. It was therefore one of the UK's best-selling magazines, most of the population had at least a passing familiarity with it, and it was both a valuable source of revenue for the corporation (unlike on television or radio, the BBC could sell advertising in the pages of the Radio Times) and a tremendous source of publicity, of immense value in promoting programmes.

This would include creatures called the Daleks - Doctor Who's first race of alien monsters. On Sunday 27th October 1963, exactly fifty years ago today, draughtsman A. Webb drew up the earliest surviving formal designs for the Daleks, from the plans of designer

This would include creatures called the Daleks - Doctor Who's first race of alien monsters. On Sunday 27th October 1963, exactly fifty years ago today, draughtsman A. Webb drew up the earliest surviving formal designs for the Daleks, from the plans of designer  Cusick worked throughout October on refining the design, consulting with other experts in the field such as

Cusick worked throughout October on refining the design, consulting with other experts in the field such as

Before Baverstock had departed on three weeks' leave, in his memo to

Before Baverstock had departed on three weeks' leave, in his memo to

That Friday evening, the second ever episode of Doctor Who to be made - the new attempt at the first episode - was due to be recorded in Studio D at Lime Grove, the same studio as the first attempt and, much to the chagrin of many of those working on the programme, allotted as Doctor Who's main studio for the foreseeable future. The production had the same cast, same director and mostly the same sets, although (as noted in the

That Friday evening, the second ever episode of Doctor Who to be made - the new attempt at the first episode - was due to be recorded in Studio D at Lime Grove, the same studio as the first attempt and, much to the chagrin of many of those working on the programme, allotted as Doctor Who's main studio for the foreseeable future. The production had the same cast, same director and mostly the same sets, although (as noted in the  What effect this had on Doctor Who's production team on the very day they were preparing to remount their opening episode is unknown. However, Sydney Newman instantly leapt to the defence of the show he had done so much bring to life. Having been given a copy of Baverstock's memo, he immediately wrote a reply pointing out that it had never been intended for the cost of the TARDIS interior set to be spread across 13 episodes - Doctor Who had originally been conceived and planned as having a 52-week run, and the costs of the set were to be covered across 52 weeks rather than 13.

What effect this had on Doctor Who's production team on the very day they were preparing to remount their opening episode is unknown. However, Sydney Newman instantly leapt to the defence of the show he had done so much bring to life. Having been given a copy of Baverstock's memo, he immediately wrote a reply pointing out that it had never been intended for the cost of the TARDIS interior set to be spread across 13 episodes - Doctor Who had originally been conceived and planned as having a 52-week run, and the costs of the set were to be covered across 52 weeks rather than 13.

In response to Wilson's memo, on Wednesday 16th October Controller of Programmes

In response to Wilson's memo, on Wednesday 16th October Controller of Programmes

However, it was an episode that would not be transmitted on British television for another 28 years.

However, it was an episode that would not be transmitted on British television for another 28 years.