The second in an occasional series marking the 50th anniversary of events leading to the creation of a true TV legend.

The second in an occasional series marking the 50th anniversary of events leading to the creation of a true TV legend.By Marcus, Chuck Foster, and John Bowman

Last time we saw how BBC Head of Script Department Donald Wilson commissioned a report into the use of science fiction in television drama. The report was compiled by two script editors for drama,

Donald Bull and

Alice Frick. Two copies of the report were sent to Wilson on

25th April 1962 - exactly 50 years ago today.

Running to three and a half pages, the typewritten report was split into two sections. The first half set out the terms of the survey and the current state of science fiction, with the second half giving a series of conclusions reached by the writers.

In compiling the report the authors had consulted previous studies of the genre by writers such as

Brian Aldiss, Kingsley Amis, and

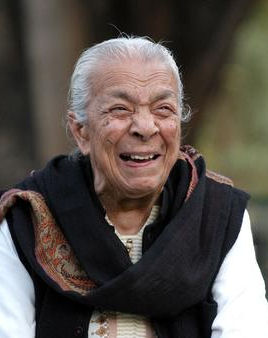

Edmund Crispin. In addition, Frick,

pictured right, had a meeting with Aldiss, the English author well-known for both general fiction and science fiction. His 1961 novel

Hothouse, which was composed of five novelettes set in a far future Earth where the planet has stopped rotating, was to win the Hugo Award for short fiction in 1962. Aldiss was then editor of Penguin science fiction in Oxford.

Previous science fiction television dramas were also studied. Of note were

The Quatermass Experiment, the

Nigel Kneale series made in 1953, and

A for Andromeda, the 1961 series written by acclaimed cosmologist

Fred Hoyle and starring

Julie Christie. It noted that both series concerned a group threat to Earth from an alien presence in which the whole of mankind was threatened.

The report stated that more people watched

The Quatermass Experiment and

A for Andromeda than liked them, adding that people weren't all that mad about sci-fi but that it was compulsive when properly presented and that the genre did not appeal much to women or older people. It advised caution, saying great care and judgment would be needed

"in shaping SF for a mass audience. It isn’t an automatic winner." The report also warned that science fiction

"so far has not shown itself capable of supporting a large population." Bull and Frick said

"the vast bulk of SF writing is by nature unsuitable for translation to TV", adding:

"SF TV must be rooted in the contemporary scene, and like any other kind of drama deal with human beings in a situation that evokes identification and sympathy." The report concluded that there was just a small group of works and writers that would be suitable for adaptation for television.

John Wyndham was noted as the chief exponent of the Threat and Disaster story, although it was pointed out that his books had been studied by the department in the past, with only

The Midwich Cuckoos being suitable for TV, a book which was not available as the rights belonged to a film company.

Arthur Clarke and

C S Lewis were also mentioned, with Lewis being dismissed as clumsy and old-fashioned. Clarke was more promising and described as a modest writer, with a decent feeling for his characters, able to concoct a good story, and a master of the ironmongery department.

Charles Eric Maine was thought too much a fantasist, obsessed with time-travel and fourth dimensions. Hoyle was considered exciting and well-related to the present day, with the potential to achieve great success.

Bull and Frick said that they couldn't recommend any existing SF stories for TV adaptation, although Clarke and Wyndham might be valuable as future collaborators. They were also adamant that it should be written by TV dramatists and not SF writers.

Two days later - on

27th April 1962 - a copy of the report was sent to

Eric Maschwitz, Assistant and Adviser to the Controller of Programmes, who had suggested to Wilson the previous month that the Survey Group look into the literary merits of science fiction for short, single adaptations.

Survey Group Report on Science Fiction:

1. We have been asked to survey the field of published science fiction, in its relevance to BBC Television Drama.

2. In the time allotted, we have not been able to make more than a sample dip, but we have been greatly helped by studies of the field made by Brian Aldiss, Kingsley Amis, and Edmund Crispin, which give a very good idea of the range, quality and preoccupations of current SF writing. We have read some useful anthologies, representative of the best SF practitioners and these, with some extensive previous reading, have sufficed to give us a fair view of the subject. Alice Frick has met and spoken with Brian Aldiss, who promises to make some suggestions for further reading. It remains to be seen whether this further research will qualify our present tentative conclusions.

3. Several facts stand out a mile. The first is that SF is overwhelmingly American in bulk. This presumably means that, if we are looking for writers only, our field is exceptionally narrow, boiling down to a handful of British writers.

4. SF is largely a short story medium. Inherently, SF ideas are short-winded. The interest invariably lies in the activating idea and not in character drama. Amis has coined the phrase "idea as hero" which sums it up. The ideas are often fascinating, but so bizarre as to sustain conviction only with difficulty over any extended treatment.

5. These remarks apply largely to the novels too. Characterisation is equally spare. People are representative, not individual. The ideas are usually nearer to Earth - in every sense - and nearer to the contemporary human situation. They are thus capable of fuller treatment in depth. By and large the differences between the short stories and the novels are also the differences between the American and British schools of SF. This again helps to limit our field of useful study.

6. SF writing falls into fairly well-defined genres. At one end is the simple adventure/thriller, with all the terms appropriately translated. Any adult interest here lies in the originality of invention and vitality of writing. On a more adult level this merges into a genre that takes delight in imaginative invention, in pursuing notions to the farthest reaches of speculation. The subtlest exponents here are a group of American writers headed by Ray Bradbury, Kathleen Maclean, Isaac Asimov. In a perhaps crude but often exciting way the apparatus is used to comment on the Big Things - the relation of consciousness to cosmos, the nature of religious belief, and like matters. The American writer Edward Blish, in "A Case of Conscience", is surpassing here. More pretentiously, far less ably, the novels of C.S. Lewis likewise use the apparatus of SF in the service of metaphysical ideas. Then comes the large field of what might be called the Threat to Mankind, and Cosmic Disaster.

Most of the novels, and most of the British work find their themes here. This is the broad mid-section of SF writing, that best known to the public and more or lees identified with SF as such. The best practitioner is John Wyndham. Exploiting instinctive psychic fears, the literature of Threat and Disaster has the most compulsive pull and probably indicates the most likely vein for TV exploitation. All "Quatermass" and "Andromeda" fall squarely into this genre. Finally, there is a small lively genre of satire, comic or horrific, extrapolating current social trends and techniques. Again, the practitioners are largely American.

7. We thought it valuable to try and discover wherein might lie the essential appeal of SF to TV audiences. So far we have little to go on except "Quatermass", "Andromeda" and a couple of shows Giles Cooper did for commercial TV. These all belong to the Threat and Disaster school, the type of plot in which the whole of mankind is threatened, usually from an "alien" source. There the threat originates on earth (mad scientists and all that jazz) it is still cosmic in its reach. This cosmic quality seems inherent in SF; without it, it would be trivial. Apart from the instinctive pull of such themes, the obvious appeal of these TV SF essays lies in the ironmongery - the apparatus, the magic - and in the excitement of the unexpected. "Andromeda", which otherwise seemed to set itself out to repel, drew its total appeal from exploiting this facet, we consider. It is interesting to note that with "Andromeda", and even with "Quatermass" more people watched it than liked it. People aren't all that mad about SF, but it is compulsive, when properly presented. Audiences - we think - are as yet not interested in the mere exploitation of ideas - the "idea as hero" aspect of SF. They must have something to latch on to. The apparatus must be attached to the current human situation, and identification must be offered with recognisable human beings.

8. As a rider to the above, it is significant that SF is not itself a wildly popular branch of fiction - nothing like, for example, detective and thriller fiction. It doesn't appeal much to women and largely finds its public in the technically minded younger groups. SF is a most fruitful and exciting area of exploration - but so far has not shown itself capable of supporting a large population.

9. This points to the need to use great care and judgement in shaping SF for a mass audience. It isn't an automatic winner.

No doubt future audiences will get the taste and hang of SF as exciting in itself, and an entertaining way of probing speculative ideas, and the brilliant imaginings of a writer like Isaac Asimov will find a receptive place. But for the present we conclude that SF TV must be rooted in the contemporary scene, and like any other kind of drama deal with human beings in a situation that evokes identification end sympathy. Once again, our field is therefore sharply narrowed.

Conclusions10. We must admit to having started this study with a profound prejudice - that television science fiction drama must be written not by SF writers, but by TV dramatists. We think it is not necessary to elaborate our reasons for this - it's a different job and calls for different skills. Further, the public/ audience is different, so it wants a different kind of story (until perhaps it can be trained to accept something quite new). There is a wide gulf between SF as it exists, and the present tastes and needs of the TV audience, and this can only be bridged by writers deeply immersed in the TV discipline.

11. Only a very cursory examination has sufficed to show that the vast bulk of SF writing is by nature unsuitable for translation to TV. In its major manifestation, the imaginative short story with philosophic overtones, it is too remote, projected too far away from common humanity in the here-and-now, to evoke interest in the common audience. Satiric fantasies are presumably out. As far as the writers themselves are concerned, nearly all of them are American, and so not available to us even if we wanted them.

We are left with a small group of works, and writers, mainly novels written by British novelists. With the exception of Arthur Clarke and C.S. Lewis, they represent the Threat and Disaster school, which as we have said, is the genre of SF most acceptable to a broad audience. John Wyndham is the chief exponent. Wyndham's books were studied in the Department on an earlier occasion, and we decided that with one exception they offered us nothing directly usable on TV. The exception was "The Midwich Cuckoos", which of course was snapped up for a film. This is indeed the likely fate of any SF novel that could also serve us for TV.

12. Two exceptions to "Threat and Disaster" are Arthur Clarke and C.S. Lewis. The latter we think is clumsy and old-fashioned in his use of the SF apparatus, there is a sense of condescension in his tone, and his special religious preoccupations are boring and platitudinous. Clarke is a modest writer, with a decent feeling for his characters, able to concoct a good story, and a master of the ironmongery department. Charles Eric Maine, who again can tell an interesting story without having to wipe out the human race in the process, is too much a fantasist: he is obsessed with the Time theme, time-travel, fourth dimensions and so on - and we consider this indigestible stuff for the audience. There is scarcely need to mention Fred Hoyle; we consider his ideas exciting, well related to the present day, and only need proper adaptation to TV to achieve great success. We consider "Andromeda" both a warning and an example.

13. It is of course not possible to say what sort of hand Clarke, say, or Wyndham, or any other practitioner would make of writing directly for TV. Perhaps their best role at present would be as collaborators, in the way we are using Hoyle. They are obviously full of specialised know-how, but only a trained TV writer could make proper use of it.

14. Our conclusion therefore is that we cannot recommend any existing SF stories for TV adaptation, and that Arthur Clarke and John Wyndham might be valuable as collaborators. As a rider, we are morally certain that TV writers themselves will answer the challenge and fill the need.

Addenda to Joint ReportI met Brian Aldiss, editor of Penguin Science Fiction (editing another volume now) in Oxford. He is very knowledgeable and has a large reference library of SF. I believe he is the Honorary Secretary of the British Science Fiction Association, and he told me of the conference mentioned by Duncan Ross. He has been engaged by Monica Sims for the "Let's Imagine Worlds in Space" programme. He will call me sometime soon and come to London, at which time he could meet someone regarding SF for television. He would be a valuable consultant - not a crank - with definite ideas about what could be achieved visually.

There are several sources of short stories which might be considered for a series of single-shot adaptations of the kind mentioned in Eric Maschwitz's memo, Perhaps the best would be the Faber (several volumes of which we have read only one) and Penguin Anthologies of Science Fiction. These seem to be the best quality short stories available.

Related Articles:

Part I (27 Mar 2012)

SOURCES: BBC Archive; The Handbook (Howe, Walker, Stammers; 2005)

Plaything of Sutekh is a new A5 Doctor Who fanzine covering all eras of the series with 40 pages and colour covers with artwork throughout. The magazine can be ordered from the website

Plaything of Sutekh is a new A5 Doctor Who fanzine covering all eras of the series with 40 pages and colour covers with artwork throughout. The magazine can be ordered from the website Featuring the tenth incarnation of the Doctor, Time Leech is a compilation of a three-part web comic originating on the Kasterborous Doctor Who news and reviews website.

Featuring the tenth incarnation of the Doctor, Time Leech is a compilation of a three-part web comic originating on the Kasterborous Doctor Who news and reviews website.

The actress

The actress

The second in an occasional series marking the 50th anniversary of events leading to the creation of a true TV legend.

The second in an occasional series marking the 50th anniversary of events leading to the creation of a true TV legend.

A documentary telling the story of BBC Television Centre is to be aired next month with contributions from many people associated with Doctor Who.

A documentary telling the story of BBC Television Centre is to be aired next month with contributions from many people associated with Doctor Who.