An Unearthly Series - The Origins of a TV Legend

Friday, 18 October 2013 - Reported by Anthony Weight

The twenty-fifth instalment of our series marking the major events in the creation of Doctor Who, fifty years to the day since they occurred.

The twenty-fifth instalment of our series marking the major events in the creation of Doctor Who, fifty years to the day since they occurred.By the middle of October, Doctor Who's path to the screen was starting to seem a little more assured and stable. The Controller of Programmes for BBC1, Donald Baverstock, had agreed to the making of at least 13 episodes, and despite the pilot episode having been rejected by Head of Drama Sydney Newman, the production team were ready for their second attempt at creating a version of the programme's opening instalment. However, on the very day the second version of An Unearthly Child was to go before the cameras, budgetary concerns led Baverstock to have a change of heart about the show's future. On Friday 18 October 1963 - exactly fifty years ago today - the Welshman dropped a bombshell. Doctor Who, still over a month away from its on-screen debut, was ordered to be brought to a halt. Production was to cease as soon as the opening four-part serial was completed...

That Friday evening, the second ever episode of Doctor Who to be made - the new attempt at the first episode - was due to be recorded in Studio D at Lime Grove, the same studio as the first attempt and, much to the chagrin of many of those working on the programme, allotted as Doctor Who's main studio for the foreseeable future. The production had the same cast, same director and mostly the same sets, although (as noted in the previous episode) the junkyard and school classroom sets had needed to be recreated by designer Barry Newbery from Peter Brachacki's plans, as they had accidentally been junked after the pilot recording.

That Friday evening, the second ever episode of Doctor Who to be made - the new attempt at the first episode - was due to be recorded in Studio D at Lime Grove, the same studio as the first attempt and, much to the chagrin of many of those working on the programme, allotted as Doctor Who's main studio for the foreseeable future. The production had the same cast, same director and mostly the same sets, although (as noted in the previous episode) the junkyard and school classroom sets had needed to be recreated by designer Barry Newbery from Peter Brachacki's plans, as they had accidentally been junked after the pilot recording.Fortunately for all concerned, the set of the TARDIS interior had not suffered this fate - had it done so, then it is highly possible that Doctor Who would have stopped for good at this point, and never made it to the screen. The high cost of the set was already controversial, and it was this element in particular that had led Baverstock to reconsider the expense involved in producing the series.

The 18th was Baverstock's last day at work before he embarked on three-weeks' leave. Despite having given the go-ahead to a 13-episode run of Doctor Who just four days previously, by Friday he had looked further into the costs involved and had sent a memo to Donald Wilson, the Head of Serials in the drama department. Wilson was one of those most closely involved in the creation of Doctor Who, and effectively the show's "executive producer" as we might now term it.

The memo was a shock - Baverstock had decided that BBC1 simply couldn't afford Doctor Who:

I am told that a first examination of your expenditure on the pilot and of your likely design and special effects requirements for the later episodes, particularly two, three and four, shows that you are likely to overspend your budget allocation by as much as £1600 and your allocation of man-hours by as much as 1200 per episode. These figures are arrived at by averaging the expenditure of £4000 on the spaceship over thirteen episodes. It also only allows for only £3000 to be spent on expensive space creatures and other special effects. It does not take account of all the extra costs involved in the operation of special effects in the studio.

Last week I agreed an additional £200 to your budget of £2300 for the first four episodes. This figure is now revealed to be totally unrealistic. The costs of these four will be more than £4000 each - and it will be even higher if the cost of the spaceship has to be averaged over four rather than thirteen episodes.

Such a costly serial is not one that I can afford for this space in the financial year. You should therefore not proceed any further with the production of more than four episodes.

Last week I agreed an additional £200 to your budget of £2300 for the first four episodes. This figure is now revealed to be totally unrealistic. The costs of these four will be more than £4000 each - and it will be even higher if the cost of the spaceship has to be averaged over four rather than thirteen episodes.

Such a costly serial is not one that I can afford for this space in the financial year. You should therefore not proceed any further with the production of more than four episodes.

Baverstock didn't entirely write-off the possibility of continuing to make Doctor Who, going on to state that he had asked the Assistant Controller of Planning, Joanna Spicer, and John Mair, the Planning Manager, to meet with all parties concerned and look into what costs might be involved in making further episodes. However, he did also tell Wilson that:

In the meanwhile, that is for the next three weeks while I am away, you should marshal ideas and prepare suggestions for a new children's drama serial at a reliably economic price. There is a possibility that it will be wanted for transmission from soon after Week 1 of 1964.

What effect this had on Doctor Who's production team on the very day they were preparing to remount their opening episode is unknown. However, Sydney Newman instantly leapt to the defence of the show he had done so much bring to life. Having been given a copy of Baverstock's memo, he immediately wrote a reply pointing out that it had never been intended for the cost of the TARDIS interior set to be spread across 13 episodes - Doctor Who had originally been conceived and planned as having a 52-week run, and the costs of the set were to be covered across 52 weeks rather than 13.

What effect this had on Doctor Who's production team on the very day they were preparing to remount their opening episode is unknown. However, Sydney Newman instantly leapt to the defence of the show he had done so much bring to life. Having been given a copy of Baverstock's memo, he immediately wrote a reply pointing out that it had never been intended for the cost of the TARDIS interior set to be spread across 13 episodes - Doctor Who had originally been conceived and planned as having a 52-week run, and the costs of the set were to be covered across 52 weeks rather than 13.The fight for Doctor Who's future, if it had one at all, and the battle over the costs of the TARDIS set would have to continue the following week. In the mean-time, there was still a series to plan and produce, whether it would make it to the screen or not. In addition to director Waris Hussein and the regular cast going back into Lime Grove to record the first episode that evening, other work was being done on the production of future episodes. Also on Friday the 18th, director Christopher Barry was busy preparing for work on what was due to be the second Doctor Who serial, the futuristic script by Terry Nation. That day, Barry sent script editor David Whitaker a detailed note of comments on the first two episodes of the serial, and also received a reply to an enquiry he had previous made to the Post Office's Joint Speech Research Unit, about how he might realise the voices of the "Dalek" creatures featured in Nation's scripts.

The unit sent Barry a tape with examples of two different types of voice, one produced using a vocoder and the other generated entirely by computer. JN Shearne, the Post Office official who supplied the material to Barry, indicated that they would only be able to produce up to 30 seconds of computer-generated material for him, due to the amount of time and effort required to programme it. The vocoder material was of greater interest to Barry, who heard something of what he wanted for the Daleks in it, but he decided that it would need to be produced in-house at the BBC rather than sourced from the Post Office, as it could then be produced live in the studio during recordings, rather than pre-recorded on tape by the Post Office. So, Barry turned his attentions to what the BBC Radiophonic Workshop might be able to do for him.

Meanwhile, the design of the actual appearance of the Dalek creatures themselves was coming towards its realisation. Originally, BBC staff designer Ridley Scott had been assigned to handle the design work for Nation's serial, but a clash of schedules meant that he was replaced by fellow department member Raymond Cusick. Cusick had taken inspiration both from the description in Nation's script of the creatures "moving on a round base," and from his own determination that the Daleks should not appear in any way human. After discussions with BBC special effects experts Bernard Wilkie and Jack Kine in early October, Cusick was working towards the final plans for his design, which was to have a massive impact on the future of Doctor Who.

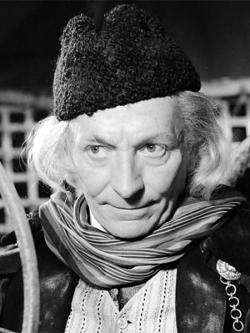

On October 18 1963, however, nobody knew that the element which would finally dispel any prospect of an early cancellation for Doctor Who was so close at hand. There was simply a television programme to produce, and the transmitted version of the very first episode was finally put onto tape that evening at Lime Grove Studios. A much smoother and more polished effort than the pilot version, with a more likeable characterisation from William Hartnell as the Doctor (as requested by Newman), there were also many other subtle differences. There was no opening thunderclap at the start of the opening titles, Susan reads a book on the French Revolution rather than drawing ink blots, and hers and the Doctor's costumes are also different.

Finally, the very first episode of Doctor Who that would be seen by viewers had been made, and the regular production of the programme was at last under way. From this point onwards, a new episode would be rehearsed and recorded every week. However, following Baverstock's memo, for how long that would be allowed to continue would be another matter.

SOURCES: The Handbook: The First Doctor – The William Hartnell Years: 1963-1966, David J Howe, Mark Stammers, Stephen James Walker (Doctor Who Books, 1994); Doctot Who Magazine issue 331 (Panini Comics, 25 June 2003)